Turned off by how churches use Bible to hurt people, pastor offers a different way

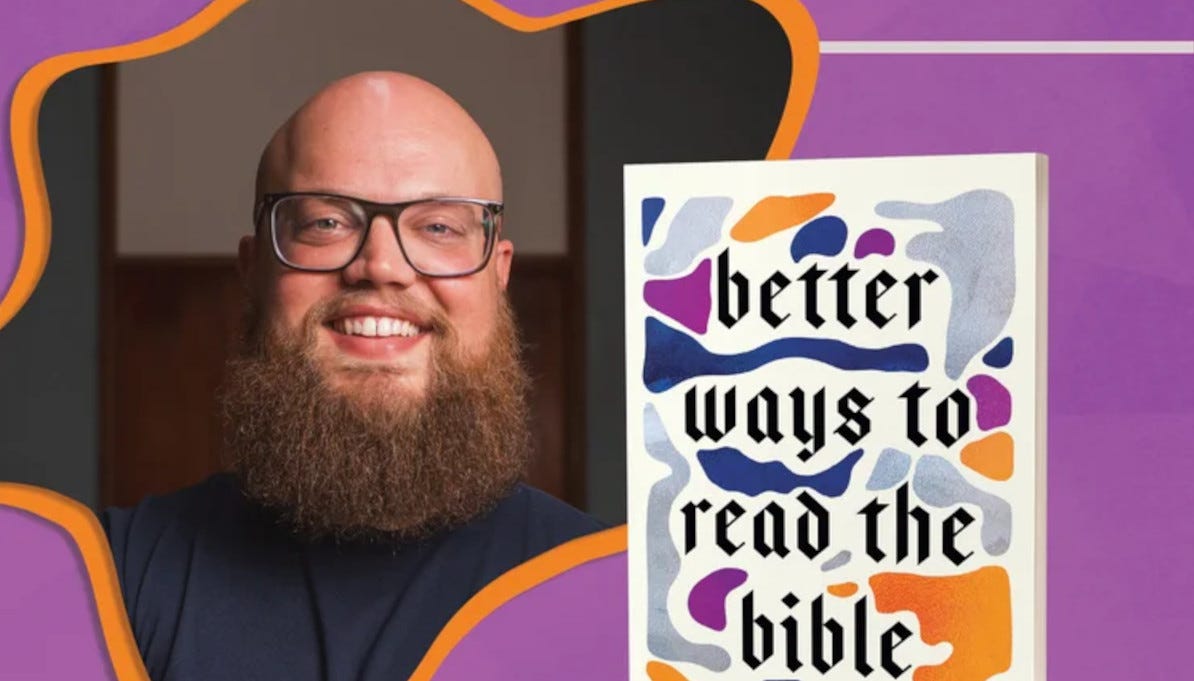

Book review: ‘Better Ways to Read the Bible: Transforming a Weapon of Harm into a Tool of Healing’ by Zach Lambert, ★★★★☆

A new type of American Protestantism could be emerging — and a book by the pastor of one its churches shows both its promises and a potential weakness.

The movement has no name yet, although it might be called something like exvangelical Christianity, for it is made up largely…