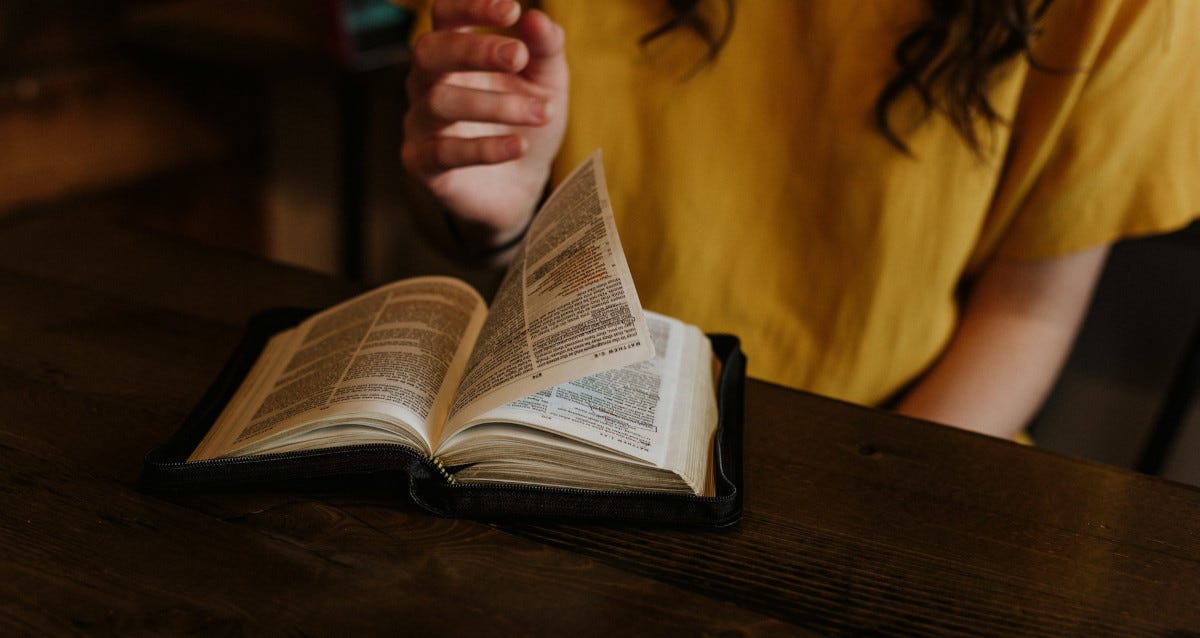

Challenging legal norms, Texas proposal would use Bible to teach kindergartners

State board considers curriculum reminiscent of new Oklahoma directives

If you want a clearer idea of exactly how Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters is trying to infuse the Bible into public classroom instruction, you need look no further than curriculum being proposed by education leaders in Texas.

A big difference, however, is that while Walters’ pla…