Blinken’s calls for protecting Gazans echo traditional Christian teaching on ‘just war’

Just-war doctrine emphasizes restraint, sometimes abstention, on military action

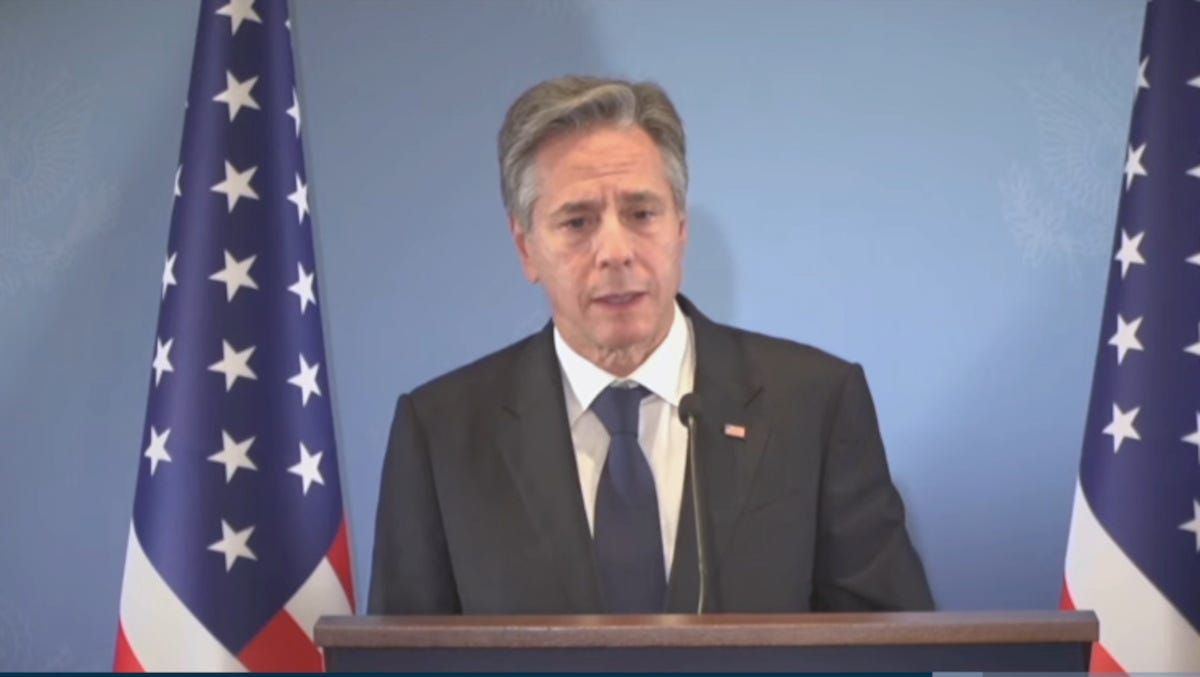

While many American evangelical Christian leaders have enthusiastically supported Israel in its war against Hamas, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s attempts this week to push Israel into doing more to protect civilians in Gaza come closer to…