Biography offers complex portrayal of world-famous missionary and author

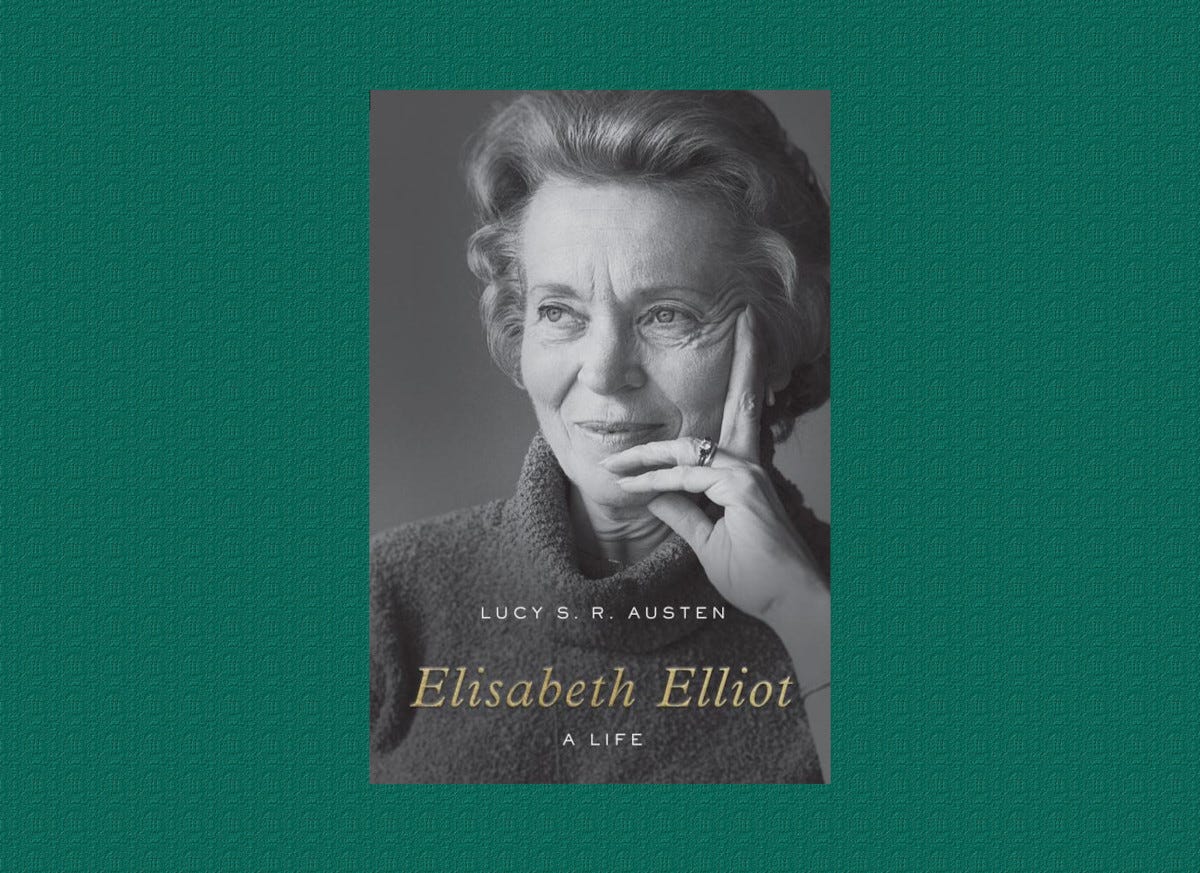

Book review: ‘Elisabeth Elliot: A Life’ by Lucy S.R. Austin, ★★★★★

It has been about a year since I read Lucy S.R. Austin’s voluminous biography of Elisabeth Elliott, but of the dozens of books I’ve read in the past few years, it’s the one that most often causes me to ponder.

Strangely enough, of the biographies I’ve read, it’s the one I read starting out with the least knowledge of the subjec…