As some Christians pursue domination, Jew calls on them to embrace pluralism

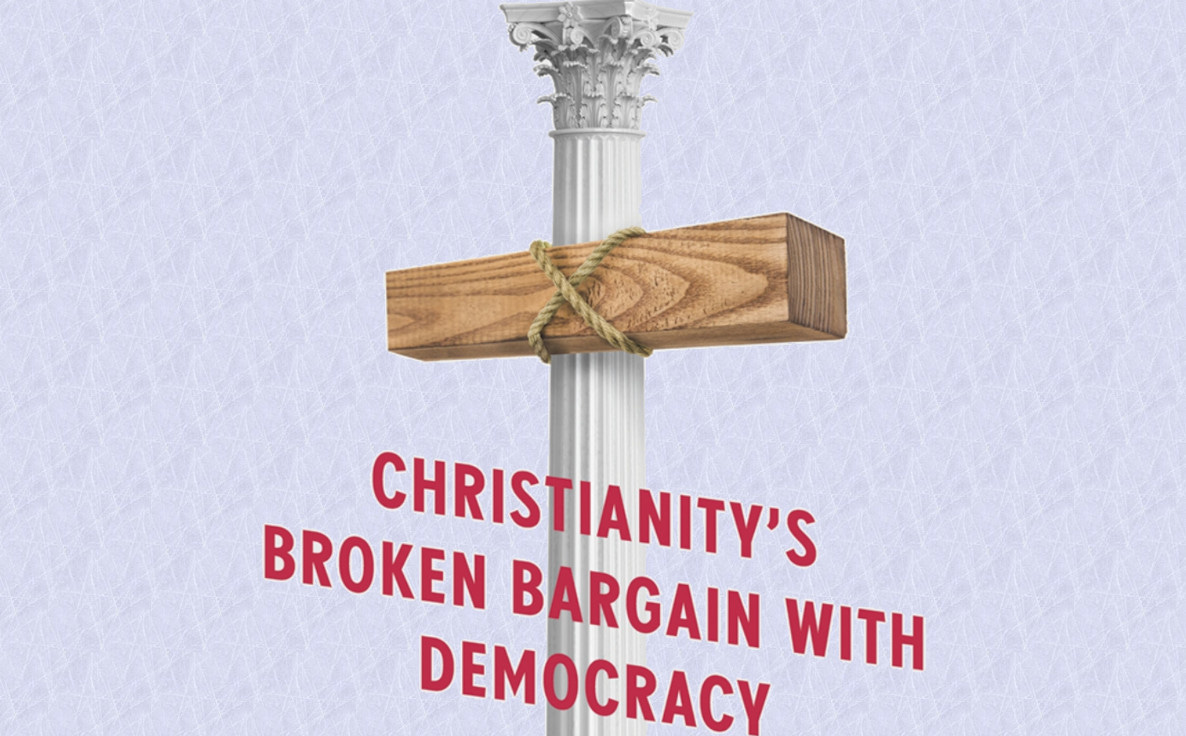

Book review: ‘Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy’ by Jonathan Rouch, ★★★★★

Jonathan Rauch believes that the writings and philosophy of James Madison have much in common with the teachings of Christianity. Furthermore, he sees the founding of the United States as having religious underpinnings, holding that neither religion nor democracy can thrive unless they are, to use hi…